News Excerpt:

Domestication can affect a species in intricate ways, forcing genetic innovation as well as handicaps.

About Silk:

- Production:

- Silk, the queen of fibers, is produced from the cocoons of the silk moth (Bombyx mori).

- Humans domesticated it more than 5,000 years ago in China, from the wild moth (Bombyx mandarina).

- The ancestral moth is today found in China, the Korean Peninsula, Japan, and far eastern Russia, whereas the domesticated moth is reared all over the world, including in India.

- India is the world’s second-largest producer of raw silk after China.

Types of Silk:

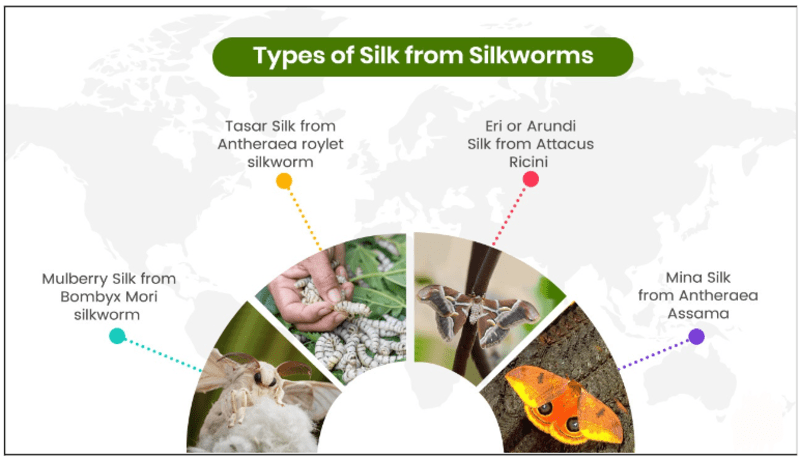

- Wild Silk:

-

- It includes the muga, tasar, and eri silks – which are obtained from other moth species: namely, Antheraea assama, Antheraea mylitta, and Samia cynthia ricini.

- These moths survive relatively independently of human care, and their caterpillars forage on a wider variety of trees.

- Non-mulberry silk:

- These silks have shorter, coarser, and harder threads compared to the long, fine, and smooth threads of the mulberry silks.

- It comprises about 30% of all silk produced in India.

- Domesticated silk moth cocoons: It comes in an eye-catching palette of yellow-red, gold, flesh, pink, pale green, deep green or white.

Cocoon’s pigments:

- The pigments are derived from chemical compounds called carotenoids and flavonoids, which are made by the mulberry leaves.

- Silkworms feed voraciously on the leaves, absorb the chemicals in their midgut, and transport them via the haemolymph – arthropods’ analogue of blood – to the silk glands, where they are taken up and bound to the silk protein.

- Mature caterpillars then spin out the silk proteins and associated pigment into a single fibre.

- The caterpillar wraps the fibre around itself to build the cocoon.

Mutant strains a valuable resource:

- The differently colored cocoons arise from mutations in genes responsible for the uptake, transport, and modification of carotenoids and flavonoids.

- The mutant strains have become a valuable resource for scientists to study the molecular basis of how artificial selection generated such spectacular diversity.

Combinations behind the colors:

- Researchers at Southwest University in Chongqing, China found that the formation of a yellow-red cocoon requires the Y gene, which encodes a protein that transports the carotenoids from midgut to the silk glands.

- Mutations in one or more of these genes produce yellow, flesh-colored, rusty, and pink cocoons.

- If the Y gene is mutated, the flavonoids are absorbed but the carotenoids are not, resulting in green cocoons.

- The green is dark or light depending on whether genes for other proteins that enhance flavonoid uptake are normal or mutated.

- If both carotenoids and flavonoids are not taken up, the cocoons remain white.

Conclusion:

Like golden retrievers, basmati rice, and alphonso mangoes, silk is the pinnacle of domestication. Presently, scientists possess the means to create and contrast genetically identical hybrid silk moths, with the only distinction being the inactivation of one of a gene's two parental versions: ancestral or domesticated.

- This opens up the possibility for scientists to decipher all the important steps leading to the domestication of the silk moth, gene by gene.