GS-1 Geography

Introduction

India's rivers, lakes, and water paths are like the veins that give life to the country. Imagine big rivers like the Ganges, Yamuna, and Brahmaputra shaping the land, culture, and people.

In this blog, we'll take an exciting trip to learn about these important waterways. We'll discover how they help farms, trade, and even connect to our traditions.

The movement of water through well-defined channels is referred to as drainage. In other words, it refers to a region's river system. A drainage system is a term used to describe the collection of these channels. An area that is drained by a single river system is called a drainage basin. Two drainage basins are separated by an elevated structure, such as a mountain or upland. An example of an upland is a water divide.

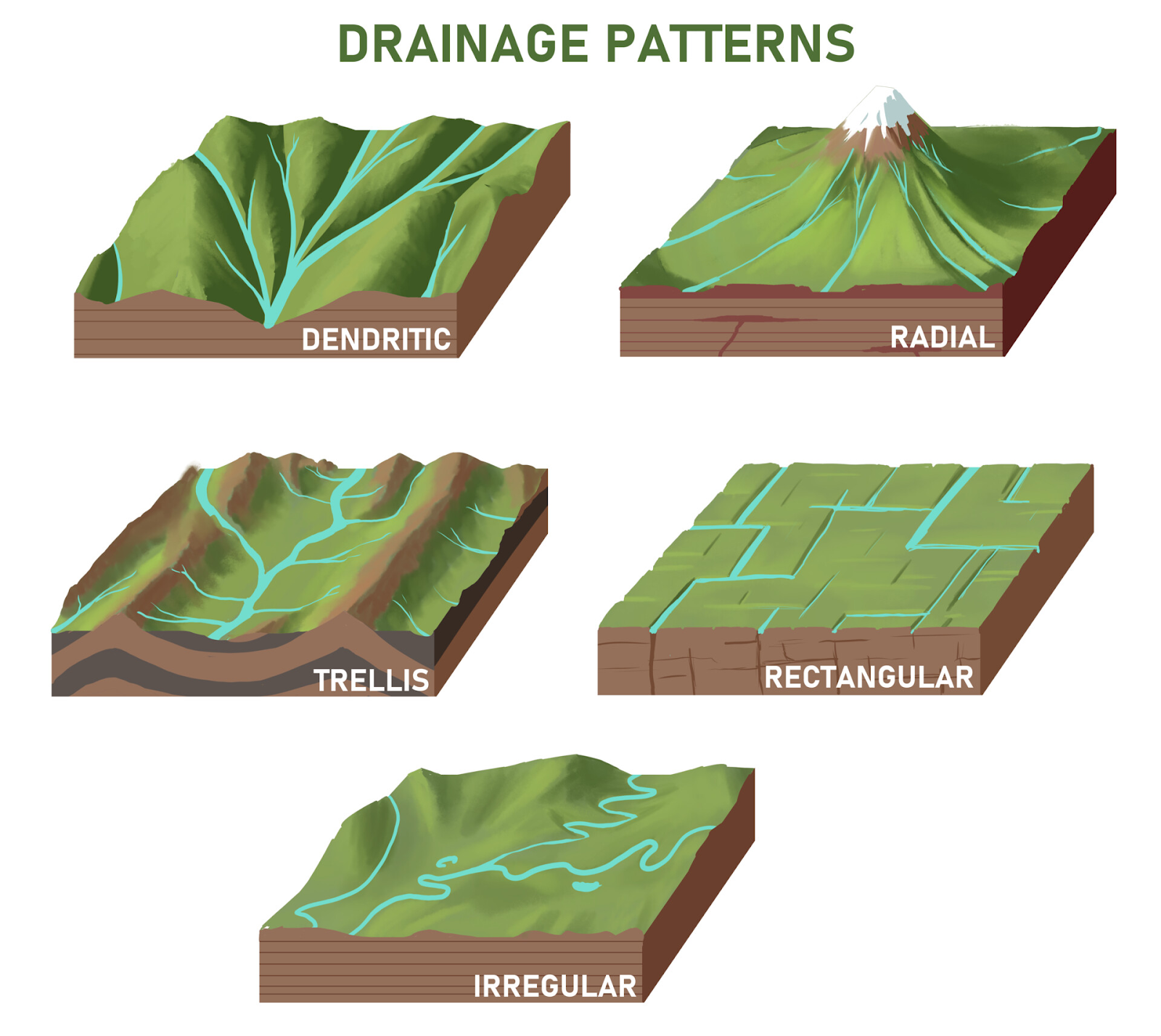

Drainage Pattern

The geological epoch, type, and structure of rocks, as well as the terrain, slope, and other factors, all affect how a region drains.

Some examples of drainage patterns are

- Dendritic- The dendritic pattern forms as the river channel follows the terrain's slope. The name "dendritic" refers to the way that the creek and its tributaries resemble tree branches. Examples: Indus, Godavari, Mahanadi

- Trellis- A trellis pattern forms when a river and its tributaries are linked at roughly right angles. Where hard and soft rocks are parallel to each other, a trellis drainage pattern forms. Example - Rivers patterns in ChotaNagpur Plateau.

- Rectangular- On a rocky landscape with many joints, a rectangular drainage pattern forms. Example - Colorado river (USA), Streams in Vindhya Ranges.

- Radial- When streams flow in diverse directions from a central peak or dome-like structure, a radial pattern forms. Best example is River Narmada flowing radially from the Amarkantak plateau. Such patterns are also found in Mikir hills of Assam.

In the same drainage basin, a mixture of many patterns may be seen.

Classification of Drainage Systems

The Indian drainage is classified based on its way of origin, nature, and features.

- The Himalayan drainage system

- The Peninsular drainage system

Let’s highlight the main differences between the two major drainage systems of India

|

Himalayan Rivers |

Peninsular Rivers |

|

|

Himalayan River Drainage System

The Indus River System

- The overall length of the Indus River system is 2,880 km (1,114 km in India).

- The Indus River originates in Tibet, near Lake Mansarovar.

- The Indus is known as Singi Khamban, or the Lion's Mouth, in Tibet.

- One of the longest rivers in the world is the Indus. A little more than a third of the Indus basin lies in India, in the states of Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, and Punjab, with the remainder in Pakistan.

- It enters India in the Ladakh area of Jammu and Kashmir, flowing west. This portion of it creates a stunning gorge. In the Kashmir area, it is joined by other tributaries, including the Zaskar, Nubra, Shyok, and Hunza.

- The Indus River passes through Baltistan and Gilgit before emerging from the mountains at Attock.

- The Satluj, Beas, Ravi, Chenab, and Jhelum rivers converge to form the Indus at Mithankot in Pakistan. Beyond this point, the Indus continues southward until it reaches the Arabian Sea east of Karachi.

- The Indus, commonly known as the Sindhu, is the westernmost of India's Himalayan rivers.

|

According to the Indus Water Treaty (1960) limits, India can only utilize 20% of the total water transported by the Indus River system. This water is utilized for irrigation in Punjab, Haryana, and sections of Rajasthan's south and west. |

The Ganga River System

- The Ganga's headwaters, known as the 'Bhagirathi,' are fed by the Gangotri Glacier and join the Alaknanda near Devprayag in Uttarakhand. The Ganga emerges from the mountains into the lowlands of Haridwar.

- Many tributaries from the Himalayas enter the Ganga, some of which are significant rivers like the Yamuna, Ghaghara, Gandak, and Kosi. The Yamunotri Glacier feeds the Yamuna River, which originates in the Himalayas.

- When it reaches Allahabad, it becomes a right bank tributary of the Ganga and continues to flow parallel to it.

- The Ghaghara, Gandak, and Kosi rivers spring in the Nepal Himalayas. They are the rivers that annually flood areas of the northern plains, causing significant harm to life and property while improving the soil for the vast agricultural regions.

- The Chambal, Betwa, and Son are the primary streams that flow from the peninsular uplands. These originate in semi-arid locations, have shorter courses, and do not transport much water.

- Water from the Ganga's right and left bank tributaries widens the river as it flows eastward toward Farakka in West Bengal. This is the Ganga Delta's northernmost point. Here, the river divides, and the distributary Bhagirathi-Hooghly travels through the deltaic plains on its way to the Bay of Bengal in the south. The Brahmaputra joins the mainstream as it flows south towards Bangladesh.

- It is known as the Meghna further downstream.

- This massive river, which receives water from the Ganga and the Brahmaputra, flows into the Bay of Bengal. These rivers contributed to the formation of the Sunderban Delta.

- The Ganga is nearly 2500 km long.

- Ambala is situated near the confluence of the Indus and Ganga river systems.

- The plains from Ambala to the Sunderban span approximately 1800 km, however, the drop in slope is just 300 meters. In other words, there is just a one-meter drop every six kilometers.

- As a result, the river forms huge meanders.

The Brahmaputra River System

- The Brahmaputra River starts in Tibet, east of Mansarovar Lake, near the Indus and Sutlej rivers' headwaters.

- It is significantly longer than the Indus and spends the majority of its time outside of India.

- It runs parallel to the Himalayas to the east. When it reaches Namcha Barwa (7757 m), it makes a 'U-turn' and enters India through a canyon in Arunachal Pradesh.

- In Assam, it is referred to as the Dihang, and it joins the Brahmaputra with the Lohit, the Dibang, and numerous other tributaries.

- Because Tibet is a cold and dry region, the river carries less water and less silt.

- It travels through a rainy region of India.

- The river here transports a high volume of water as well as a significant amount of silt. In Assam, the Brahmaputra River has a braided channel that generates several riverine islands.

- Every year during the rainy season, the river breaches its banks, inflicting extensive destruction in Assam and Bangladesh due to floods. Unlike other north Indian rivers, the Brahmaputra has massive layers of silt on its bed, which causes the river to rise. The river's course also changes often.

Peninsular River Drainage System

The peninsular drainage system is older than the Himalayan rivers.

The Western Ghats, which extend from north to south close to the western shore, create the primary water divide in Peninsular India.

The majority of the Peninsula's major rivers, including the Mahanadi, Godavari, Krishna, and Kaveri, run eastward and discharge into the Bay of Bengal. At their mouths, these rivers form deltas. A number of tiny streams flow west of the Western Ghats.

The only long rivers with a western flow and estuaries are the Narmada and Tapi Rivers. The peninsular rivers' drainage basins are rather limited in size.

The Narmada Basin

- The Narmada River springs in Madhya Pradesh's Amarkantak hills.

- It runs westward via a rift valley caused by faulting.

- Madhya Pradesh and Gujarat are the home of the Narmada basin.

- The Narmada provides several gorgeous places on its approach to the sea.

- Some of the most remarkable are the Marble Rocks at Jabalpur, where the Narmada runs through a deep valley, and the 'Dhuandhar Falls,' where the river plunges over high cliffs.

- The Narmada's tributaries are all quite short, and the majority of them enter the mainstream at right angles.

The Tapi Basin

- The Tapi begins in the Satpura mountains of Madhya Pradesh's Betul district.

- It likewise runs in a rift valley parallel to the Narmada, although its length is significantly less.

- Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, and Maharashtra are all part of its drainage basin.

- The main west-flowing rivers are Sabarmati, Mahi, Bharathpuzha, and Periyar.

- The coastal lowlands that connect the Western Ghats to the Arabian Sea are quite narrow.

- As a result, the coastal rivers are short.

The Godavari Basin

- The Godavari is the biggest river on the peninsula.

- It rises from the foothills of the Western Ghats in Maharashtra's Nashik district.

- It is approximately 1500 kilometers long.

- It empties into the Bay of Bengal.

- It also has the largest drainage basin of any peninsular river.

- The basin includes sections of Maharashtra (approximately half of the basin area), Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, and Andhra Pradesh.

- The Godavari receives water from a number of tributaries, including the Purna, Wardha, Pranhita, Manjra, Wainganga, and Penganga. The last three tributaries are massive.

- It is also known as the 'Dakshin Ganga' due to its length and the territory it spans.

The Mahanadi Basin

- The Mahanadi River rises in the Chhattisgarh highlands.

- It runs across Odisha on its way to the Bay of Bengal.

- The river runs for around 860 km. Maharashtra, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, and Odisha all share their drainage basins.

The Krishna Basin

- The Krishna River runs for around 1400 km from a source in Mahabaleshwar to the Bay of Bengal.

- The Tungabhadra, Koyana, Ghatprabha, Musi, and Bhima are some of its tributaries.

- Maharashtra, Karnataka, and Andhra Pradesh share their drainage basins.

The Kaveri Basin

- The Kaveri River begins in the Western Ghats' Brahmagiri range and flows into the Bay of Bengal south of Cuddalore, Tamil Nadu.

- The river's total length is around 760 km.

- Its main tributaries include Amravati, Bhavani, Hemavati, and Kabini.

- Its basin provides drainage for a portion of Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and Karnataka.

Conclusion

In conclusion, India's natural drainage systems, encompassing rivers, lakes, and wetlands, hold immense significance for the nation's environment, economy, and society. From supporting agriculture and water supply to fostering biodiversity, enabling transportation, and providing cultural value, these systems play a pivotal role in various aspects of Indian life. However, careful management and preservation are vital to ensure their continued benefits amidst challenges like pollution and climate change. Balancing development with conservation is essential for a sustainable and prosperous future.