GS Paper II

News Excerpt:

The recent Supreme Court hearing on the constitutionality of electoral bonds has focused attention on an issue that goes to the heart of Indian democracy: the funding of political parties.

What is the funding of Political Parties?

- Political party funding is a method used by a political party to raise money for campaigns and routine activities.

- The funding of political parties is an aspect of campaign finance.

- Political parties are funded by contributions from multiple sources.

About the Campaign Financing:

- Campaign finance, also known as election finance, political donations or political finance, refers to the funds raised to promote candidates, political parties, or policy initiatives and referendums. Donors and recipients include individuals, corporations, political parties, and charitable organisations.

A campaign finance framework should respond to different political systems. For instance -

- The US elections revolve around individual candidates’ campaign machinery. Even national presidential campaigns are run, in large part, by individual candidates.

- On the other hand, in India, like in most other parliamentary systems, parties are central to electoral politics. The primary focus of the campaign finance framework in India needs to be parties, not individual candidates.

Indian electioneering is no longer restricted to parties and candidates. There has been a staggering rise in the involvement of political consultancies, campaign groups and civil society organisations in online and offline political campaigns.

A fruitful party funding framework requires attention to at least four key aspects:

- Regulation of Donations:

-

- Donations banning: Some individuals or organisations, for instance, foreign citizens or companies, may be banned from making any donations.

- Donation limits: They are aimed at ensuring that a party is not captured by a few large donors — whether individuals, corporations, or civil society organisations.

- Therefore, some jurisdictions rely on contribution limits for regulating the influence of money in politics.

- Contribution limits are aimed at avoiding a political party capture.

- For instance, the US federal law imposes different contribution limits on different types of donors.

- Expenditure limits:

- Expenditure limits safeguard politics from a financial arms race.

- It relieves parties from the pressure of competing for money before they even start to compete for votes. Therefore, some jurisdictions impose an expenditure limit on political parties.

- In the UK, for instance, a political party is not allowed to spend more than £30,000(approximately 30 Lakh rupees) per seat contested by that party.

- However, the US Supreme Court’s highly expansive interpretation of the First Amendment (freedom of expression) has been a major roadblock for various legislative attempts at imposing expenditure limits

- Public Funding:

-

- A publicly funded election is an election funded with money collected through income tax donations or taxes as opposed to private or corporate funded campaigns.

- It is an attempt to move toward a one voice, one vote democracy, and remove undue corporate and private entity dominance.

- Jurisdictions such as the United Kingdom, Norway, India, Russia, Brazil, Nigeria, and Sweden have considered legislation that would create publicly funded elections.

- Broadly, there are two ways of implementing public funding:

- Predetermined criteria: The most commonly used method around the world is to set predetermined criteria. For instance, in Germany, parties receive public funds on the basis of their importance within the political system.

- Generally, this is measured on the basis of the votes they received in past elections, membership fees, and the amount of donations received from private sources.

- Moreover, German “political party foundations” receive special state funding dedicated to their work as party-affiliated policy think tanks.

- Democracy vouchers: It is a relatively recent experiment in public funding. This is in place for local elections in Seattle, US. Under this system, the government distributes a certain number of vouchers to eligible voters.

- Each voucher is worth a certain amount. The voters can use these vouchers to donate to the candidate of their choice.

- While the voucher is publicly funded, the decision to allocate the money is taken by individual voters.

- However, some recent studies have pointed out that while this system may be more egalitarian, it may also promote more extremist candidates.

- Predetermined criteria: The most commonly used method around the world is to set predetermined criteria. For instance, in Germany, parties receive public funds on the basis of their importance within the political system.

- More generally, one of the problems with public funding is that unless we decide to ban private funding altogether (likely to be a tall ask in India), public funding only tops up party funds; it does not solve the challenging task of regulating private money.

- Disclosure Requirements:

-

- It is a less intrusive form of regulation and thus, does not outrightly prevent parties or donors from receiving or making donations.

- Disclosures nudge voters against electing politicians who have used or are likely to use their public office for quid pro quo arrangements. As such, it may discourage parties from using public office to benefit their donors.

- Disclosure as regulation rests on an assumption that the information supply and public scrutiny may influence politicians’ decisions and the electorate’s votes. However, mandatory disclosure of donations to parties is not always desirable.

- At times, donor anonymity serves a useful purpose of protecting donors. For instance, donors may face the fear of retribution or extortion by the parties in power. The threat of retaliation may, in turn, deter donors from donating money to parties of their liking.

Striking a balance between Anonymity and Transparency:

- Many jurisdictions have struggled with striking an appropriate balance between the two legitimate concerns — transparency and anonymity.

- They strike this balance by allowing anonymity for small donors while requiring disclosures of large donations. For instance, in the UK, a political party needs to report the donations received from a single source amounting to a total of more than £7,500 (roughly Rs. 7,50,000) in a calendar year.

But the effort seems unworkable: The analogous limits in the argument in favour of this approach goes as follows: small donors are likely to be the least influential in the government and most vulnerable to partisan victimisation. On the other hand, large donors are more likely to strike quid pro quo arrangements with parties.

A Chilean experiment: To reap the benefits of anonymity, and yet, prevent quid pro quo arrangements.

- Under the Chilean system of “reserved contributions”, the donors could transfer the money they wished to donate to parties to the Chilean Electoral Service.

- The Electoral Service would then forward the sum to the party without revealing the donor’s identity.

- Despite the complete anonymity in Chile, the parties are still striking quid pro quo arrangements.

- This is evident as various scandals revealed in 2014-15, Chilean politicians and donors had coordinated with each other to effectively erode the system of complete anonymity.

India’s Challenges:

- In India, there are no donation limits on individuals. Moreover, the Finance Act of 2017 also removed any official contribution limits on companies.

- No legal expenditure limit on expenditure by political parties: A party can spend as much as it wants for its national or state-level campaign as long as it does not spend that money towards the election of any specific candidate.

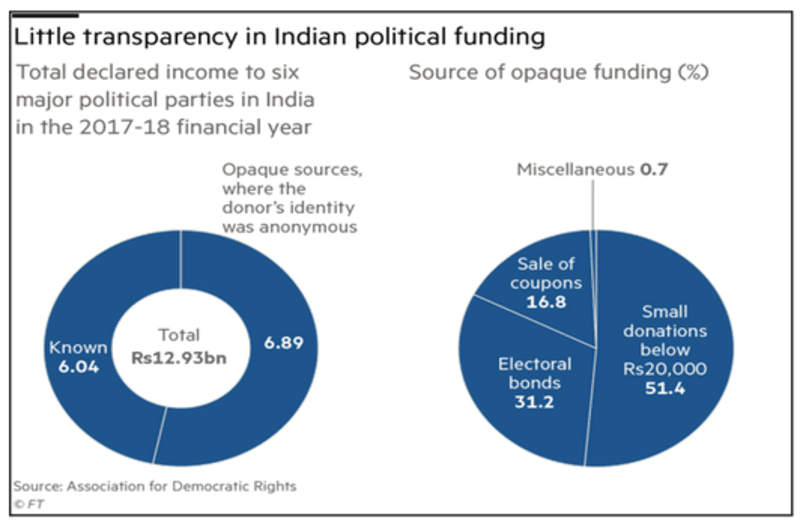

- However, parties are required to disclose donations of more than Rs 20,000, unless they are made through electoral bonds. Parties are not required to disclose the sum or the source of any single donation that is below Rs 20,000. This is where the legal loophole steps in — parties generally break large donations from a single donor into multiple small donations. This practice exempts them from any disclosure requirement.

Electoral bond Mess:

- Electoral bonds helped to strike quid pro quo deals without any public scrutiny: Since 2017, electoral bonds have enabled large donors to hide their donations if they use official banking channels.

- Even more importantly, the ability of the party in power to access the information about donors of other parties (through law enforcement agencies) undermines the scheme of electoral bonds on its own terms, i.e., to prevent victimisation of donors.

Conclusion:

Indian electioneering is no longer restricted to parties and candidates. Over the last decade, we have seen a staggering rise in the involvement of political consultancies, campaign groups and civil society organisations in online and offline political campaigns.

Mains PYQ

Q. Some of the International funding agencies have special terms for economic participation stipulating a substantial component of the aid used for sourcing equipment from the leading countries. Discuss the merits of such terms and there exists a strong case not to accept such conditions in the Indian context. (UPSC 2014)