Who’s the big boss of the global south?

Relevance: GS Paper II

Why in News?

The term "the global south" has gained popularity recently, but its limitations are evident. It cannot fully capture the complexities of over 100 countries, from Morocco to Malaysia. Despite this, it has been adopted by prominent figures like Joe Biden, Emmanuel Macron, and Xi Jinping.

Definition of the Global South:

- The global south refers to most non-Western countries and emerging economies seeking more power over global affairs.

- They often criticise Western policy, such as the war in Gaza and Western decisions on Ukraine, COVID-19, and climate policy.

- Sarang Shidore of the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft, an American think-tank, suggests that the global south is more of a geopolitical fact than a coherent grouping.

Leadership claims:

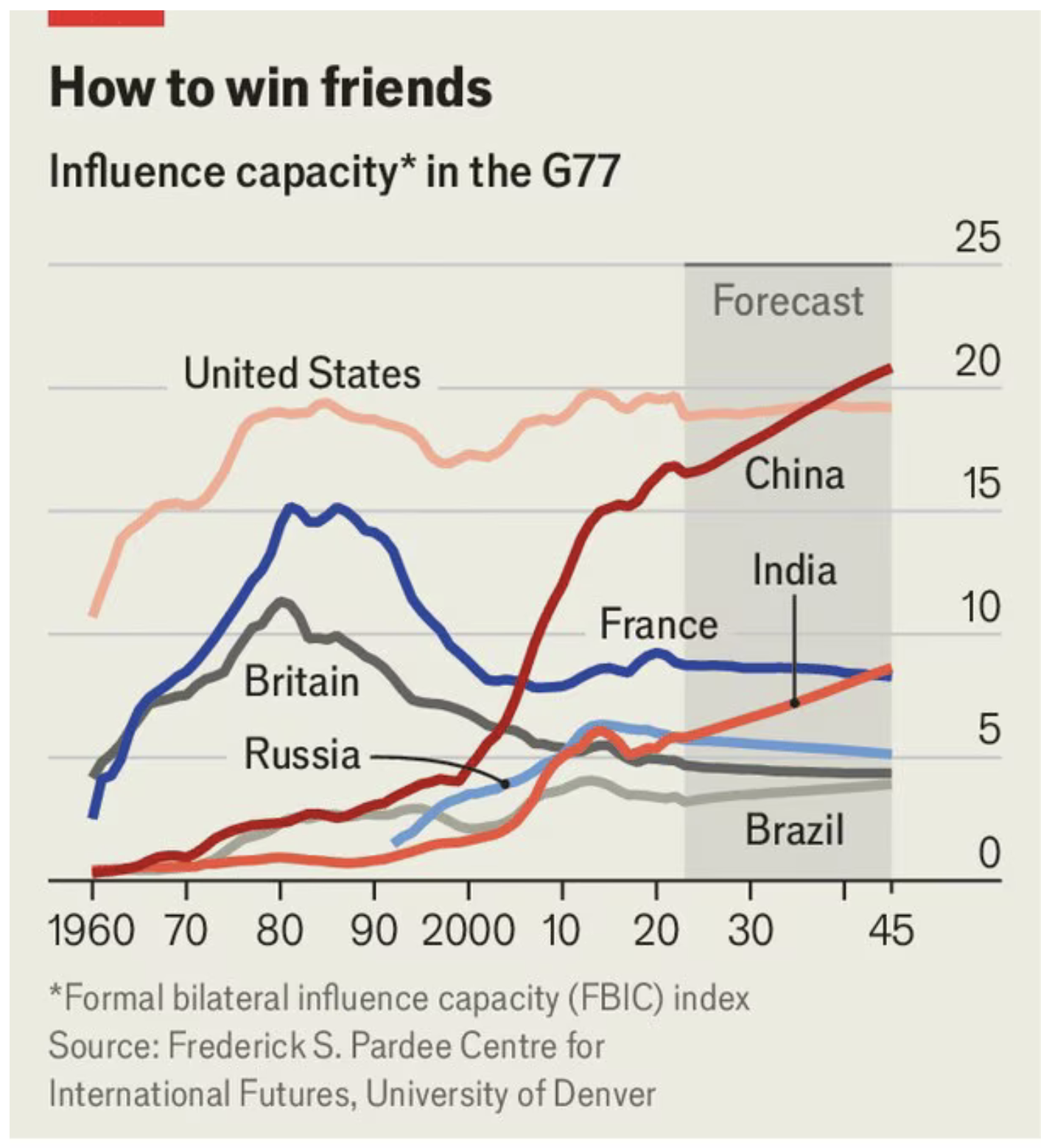

- The Pardee Centre for International Futures (PCIF) at the University of Denver has built an index of states’ power from 1960 to 2022. The main metric is known as “formal bilateral influence capacity," a measure of how much power country A may have over country B based on two dimensions.

- First, there is “bandwidth," or the extent of connections back and forth: the volume of trade, diplomatic representation, and so on.

- Second, “dependence" refers to how much country B needs country A’s arms, loans, investments, etc.

- More connections mean more chances for country A to exert influence—and asymmetry in power makes it easier to do so.

- Think of China’s power over Pakistan, for instance, ample connections, and China enjoys asymmetric influence.

- The exercise examines power relations among the 130-odd members of the global south found in the G77, a UN grouping.

- America has been the country with the most influence over the G77 since the 1970s. Its “influence capacity" has been more or less constant even as the allure of Britain and France has waned. But it is increasingly rivalled by China.

- China, after 40 years of relative insignificance, saw its influence grow from around 2000. China’s “influence capacity" over the G77 is roughly double that of France, the third-most influential country, and around three times that of Britain, India, or the UAE.

China's increasing influence:

- Rapid expansion of influence: China wields the most influence in 31 countries. Its clout is greatest in Pakistan, Bangladesh, Russia, and several other South-East Asian states.

- India, the second-most powerful member of the global south, has only six G77 members.

- According to an earlier analysis by PCIF, from 1992 to 2020, the number of countries over which China had more influence than America almost doubled, from 33 to 61.

- Embracing the Global South identity: Recently, China has become much more keen on the whole idea of grouping.

- Last year, Mr Xi and senior Chinese officials began referring to their country as part of the “global south," a description they had hitherto resisted (the term is credited to an American left-wing academic in the 1960s) in favour of phrases like “family of developing countries."

- China published proposals in September on changing international institutions, rules, and laws.

- It claimed this was a vision of “true multilateralism" where “universal security" replaced “universal values"—in other words, a system not run by an interfering West.

- Belt and Road Initiative (BRI): China is intensely strategic about winning influence and targets swing states with infrastructure support, financing and more.

- From 2000 to 2021, it funded over 20,000 infrastructure projects, many of which were under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), across 165 countries with aid or credit worth $1.3trn.

- Some analysts have noted data showing that credit from large state-backed lenders such as the Export-Import Bank of China is drying up.

- However, a paper published in November by AidData argues otherwise. “Contrary to conventional wisdom, Beijing is not in retreat".

- The paper finds that many more entities are extending credit to the developing world today: in 2021, it counted lending of $80bn a year. “[China] remains the single largest source of international development finance in the world."

- Geopolitical manoeuvring: China is targeting geopolitical fence-sitters. AidData reckons that around two-thirds of Chinese financing goes to “toss-up" countries, where neither China nor America clearly holds sway.

- The group has identified a quid pro quo. If a government increases its share of votes at the UN General Assembly (UNGA) that aligns with China’s by ten percentage points, it can expect an average 276% increase in financing from Beijing.

- China has also used its weight to curry favour on subjects such as its repression in Xinjiang. From 2000 to 2021, “low- and middle-income countries" voted on foreign-policy decisions with China 75% of the time at the UNGA.

- Economic engagement: China uses other tools, too. It is the main trading partner of more than 120 countries and has provided $240bn, mostly since 2016, in emergency financing of the sort the IMF specialises in.

- China also builds infrastructure projects quickly in developing countries, pleasing their elites and subsidising the roll-out of digital tech, such as Huawei.

- Over the past five years, it has overtaken Russia as the main source of weapons for sub-Saharan Africa.

Challenges to China's Leadership:

- Limited reach and intensity of influence: Recent polls in Africa and Southeast Asia, for example, show split support for America and China in developing countries.

- Concerns over China's conduct and political values: Its actions in business and politics have attracted calls for accountability, and countries sometimes lay the blame for their debt crises at its door.

- China’s disdain for values-based interactions (it preaches non-interference instead) is apparent. Most of the one-party state’s closest allies are also autocratic.

- Places in the global south where democratic values are considered strong, such as Brazil, are unlikely to have a close cultural connection with China.

- China draws nearer to the likes of Iran and Russia, and it risks allying with countries that want to destroy, rather than reform, the international order.

- Economic reputation concerns: China’s economic reputation could deteriorate. The public support it won through its lending binge happened before the money needed repaying. Some 75% of its BRI loans will require the principal to be paid back by 2030.

- According to Afrobarometer, a pollster, the share of people in Africa who see China as having a positive impact on their development dipped from 59% to 49% from 2019 to 2022.

- Mr Xi’s latest response to China's economic woes is to launch massive industrial subsidies, which could lead to manufactured goods flooding the markets of other emerging economies. Although some consumers may benefit, another “China shock" may stunt the industrial ambitions of governments in the global south.

Emergence of India:

- Even as China faces headwinds, new rivals are emerging, and their influence in the global south is rising. India is the front-runner.

- The number of Indian embassies in Africa increased from 25 to 43 between 2012 and 2022.

- It is the continent’s fourth-largest trade partner and fifth-largest source of foreign direct investment.

- Meanwhile, India is also offering its “stack" of digital platforms—including biometric identity technology—to countries such as Ethiopia, Sierra Leone and Sri Lanka.

- Some of India’s power is unquantifiable. With its ultra-pragmatic foreign policy, India has forged closer bonds with America while refusing to condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. It is closer to the median worldview among the G77 than China.

- India’s pitch to lead is also substantively different. Because it worries more about a China-led Asia than an American-led world, it is also pragmatic about its approach to reforming international rules. The country wants to be a bridge to the West.

Diversity of power dynamics within the global south:

- Other countries have specialist claims to power. If China is a supermarket of influence, then its rivals in the global south are like boutiques, offering other members a smaller range of bespoke goods.

- Gulf states are investing some of their hydrocarbon windfalls in renewable-energy projects and mines in the developing world.

- Brazil, the world’s second-largest agricultural exporter, is using its chairmanship of the G20 this year to promote food security in the global south.

- South Africa sees itself, improbably, as the moral leader of the global south, taking Israel to the International Court of Justice for alleged genocide in Gaza and leading a “peace mission" of African countries to Ukraine and Russia.

- Lastly, America and its allies are not out of the game. Rich countries in the OECD group spend more than $200bn annually in overseas aid (loans make up most of China’s financing).

- According to IMF data, trade between sub-Saharan Africa, America, and the euro area is greater than that between the region and China. In addition to alliances like NATO, America has defence partnerships with 76 countries.

- China hopes to see off this competition. Yet even if it does, it will be the leading power in a group that will never be cohesive.

- China is not going to welcome India permanently onto the UN Security Council;

- Brazil and South Africa regularly disagree at the WTO over agriculture;

- Debtor countries and creditors like China want different things from the reforms of the World Bank and the IMF.

Conclusion:

China has emerged as a significant player within the global south. However, its leadership faces challenges due to the diverse interests and complexities within the region. Other countries, such as India, also present alternative leadership models. Countries in the global south prioritise their national interests, often leading to conflicts with other nations, including the West and China. The global south, in other words, does not want a leader. It is a zone of contest.

Mains PYQ:

Q. “The USA is facing an existential threat in the form of China, that is much more challenging than the erstwhile Soviet Union.” Explain. (UPSC 2021)

Q. ‘China is using its economic relations and positive trade surplus as tools to develop potential military power status in Asia’, In the light of this statement, discuss its impact on India as her neighbour. (UPSC 2017)

Q. At the international level, the bilateral relations between most nations are governed on the policy of promoting one’s own national interest without any regard for the interest of other nations. This leads to conflicts and tensions between the nations. How can ethical consideration help resolve such tensions? Discuss with specific examples. (UPSC 2015)